– Kirsten Nickles, Dr. Alejandro Relling and Dr. Anthony Parker, the Ohio State University Animal Science Department

Since the mid 1990’s, Ohio has experienced an increase in the number of precipitation events greater than 2 inches (Frankson and Kunkel, 2017), with winter rainfall increasing and snowfall decreasing (Hayhoe et al., 2010). Winter and spring precipitation are expected to increase 20 – 30% further by the end of the century (Hayhoe et al, 2010) and summer precipitation is expected to remain the same or decrease slightly (Wuebbles and Hayhoe, 2004). As a result of these climatic changes, beef producers are dealing with more mud in pastures and lots, and this has a bigger effect on the beef cow herd than you may think.

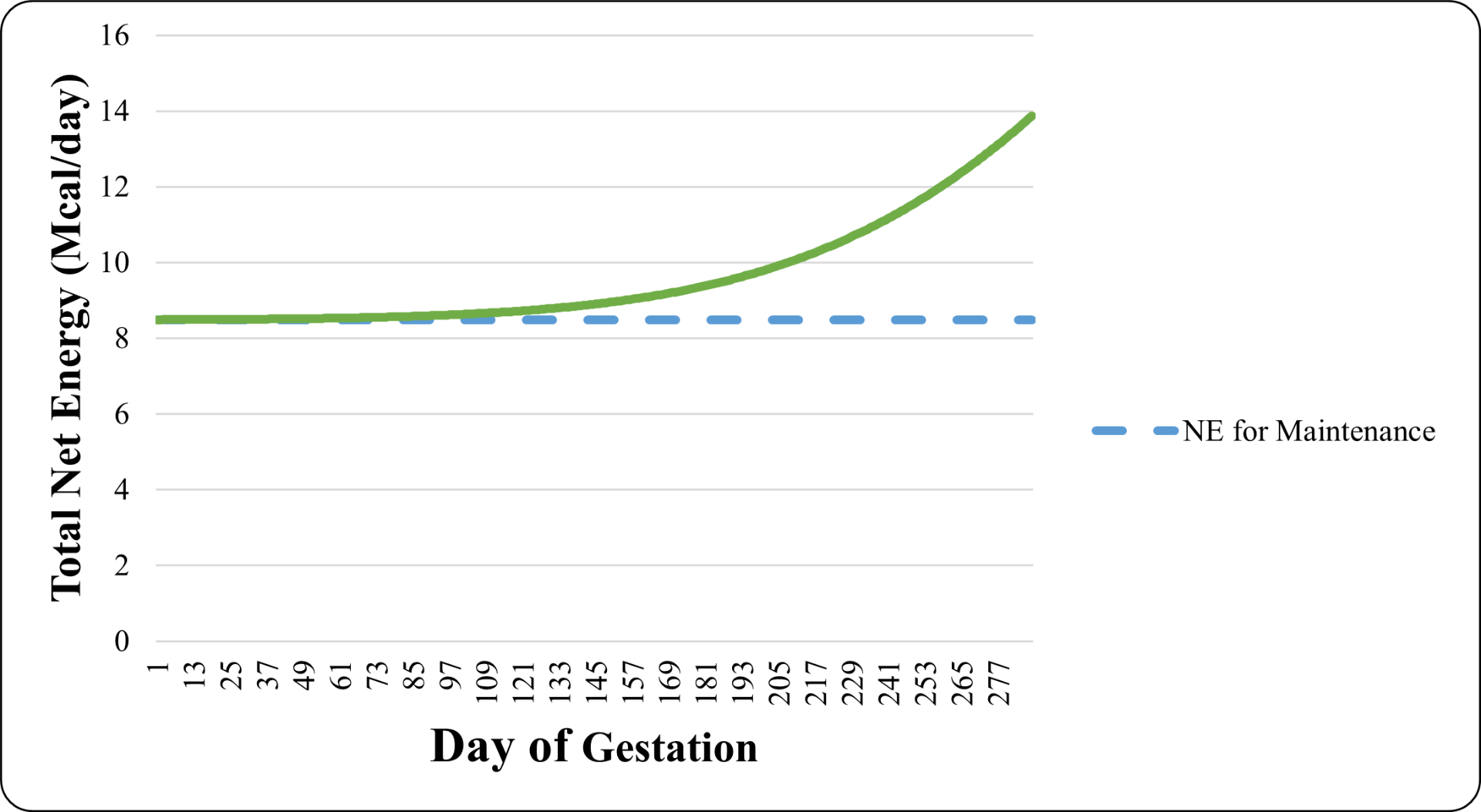

In spring calving beef cow herds, females are typically in the last third of gestation from January to March. The last trimester of gestation is when most fetal growth occurs, with an Angus type fetus growing approximately 0.9 lbs/day towards the end of the third trimester. The rapid growth of the fetus at this time requires the cow to meet the fetal nutrient requirements by increasing her nutrient intake and/or mobilizing her body tissues. Figure 1 demonstrates the increase in nutrient requirements for maintenance and throughout gestation. At thermoneutral conditions, a 1200 lb non-pregnant and non-lactating cow, requires 8.5 Mcal Net Energy/day to maintain her body weight. At the end of gestation, the same cow requires 14 Mcal Net Energy/day to maintain her body weight and meet the requirements for the growth of a 77 pound calf.

Figure 1. The total net energy requirements (Mcal/d) for maintenance (Dotted blue line) and maintenance + gestation (Solid green line) for a 1200lb beef cow giving birth to a 77 pound calf.

When beef cows are exposed to wind, rain, and mud the nutrient requirements to maintain body weight and grow a fetus increase in part because the insulative properties of the hair coat are compromised, and the cow must increase her rate of metabolic heat production to maintain her internal body temperature (Webster et al., 1970; Webster, 1974; Young, 1983). It has also been proposed that cattle expend more energy when walking through mud compared to the energy they require to walk on dry ground, but there is limited supporting data for this assumption in cold environments. Cows exposed to muddy conditions change their behavior by spending a greater amount of time standing and less time lying in mud compared to cows given access to bark chip bedding and this alone requires greater energy expenditure by the cow.

In the winter of 2019, Kirsten Nickles, a PhD candidate, conducted research at The Ohio State University to determine the energy cost of a muddy environment to beef cows throughout late gestation. Cows with similar body weight were paired and allocated to either a mud pen with an average depth of 9.3 ± 2.3 inches, or a bark chip bedded pen of a similar depth. Treatments were applied to the cows from day 213 to day 269 of gestation. Although each pair of cows were fed the same amount of feed, the cows in the mud pens weighed 83 pounds less than cows in the bark chip pens and lost one body condition score by the end of the study on day 269 of gestation. Calf birth weight was not affected by the mud treatment; however, cows subjected to mud pens decreased their conceptus free body weight indicating that the cows mobilized body tissues for fetal growth. Cows in the bark chip bedding group maintained their conceptus free body weight throughout the treatment period. Nickles and her colleagues estimated the cows in the mud treatment would have needed an extra 1.8 Mcal Net Energy/day to maintain their conceptus free body weight.

The typical quality of hay fed to gestating cows in Ohio limits the cow’s dry matter intake because of the concentration of neutral detergent fiber (NDF) present in the hay. Beef cows can generally eat approximately 1.2% of their body weight in NDF; but when dealing with poor quality forages, cows cannot consume enough forage to meet the requirements for maintenance and gestation. If environmental conditions such as mud increase energy requirements further than the net energy required for maintenance and gestation, then the cow must mobilize her body tissues to meet her energy demands. In mobilizing her body tissues to meet her energy requirements, the cow will lose body weight, and this can create other long term problems. Cows with reduced body weight and body condition scores will have decreased colostrum quality, longer postpartum intervals, increased days to conception, and decreased pregnancy rates (Corah et al., 1975; Soca et al., 2013; Selk et al., 1988; Perry et al., 1991). In addition, Soca et al. (2013) found that cows with a body condition score of 4.5 or greater at calving and cows that were gaining body condition after calving had greater pregnancy rates than cows that had body condition scores of 4 or less or that had lost body condition after calving. These results indicate that nutrient restriction prepartum should be avoided unless you are willing to heavily supplement cows after calving.

The effects of mud on nutrient requirements are not known for first calf heifers. We are currently conducting research in the winter of 2020 and spring of 2021 to determine the effects that mud has on first calf heifer nutrient requirements and reproduction after calving. As previously mentioned, cows housed for the last trimester of gestation in muddy conditions had an estimated increase in energy requirements of 1.8 Mcal Net Energy/day, which is equivalent to approximately 20% of the daily energy requirements for maintenance of a 1200 lb cow. While this restriction did not affect calf birth weight from mature cows, it is likely that if cows are not supplemented heavily after calving there will be an increased postpartum intervals and decreased pregnancy rates that can negatively impact the financial stability of the cow-calf operation.